The Yield Curve and Predicted GDP Growth, October 2013

November 5, 2013

Covering October 5, 2013–October 18, 2013

Highlights

| October | September | August | |

| 3-month Treasury bill rate (percent) | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| 10-year Treasury bond rate (percent) | 2.66 | 2.64 | 2.73 |

| Yield curve slope (basis points) | 258 | 262 | 268 |

| Prediction for GDP growth (percent) | 1.1 | 0.9 | |

| Probability of recession in 1 year (percent) | 2.12 | 2.23 |

Overview of the Latest Yield Curve Figures

Concerns over the debt ceiling apparently had some impact on the shorter end of the yield curve, pushing the three-month Treasury bill rate up to 0.08 percent (for the week ending October 18), the highest level since March and a big jump up (at these low levels, anyway) from September’s 0.02 percent and even August’s 0.05 percent. The ten-year rate moved up, but not as much (either absolutely or proportionally) to 2.66 percent, above September’s 2.64 percent, but below August’s 2.73 percent. The slope decreased to 258 basis points, down from September’s 262 basis points, and August’s 268 basis points.

The steeper slope had a negligible impact on projected future growth. Projecting forward using past values of the spread and GDP growth suggests that real GDP will grow at about a 1.2 percentage rate over the next year, even with September’s rate and just up from August’s rate of 1.1 percent. The influence of the past recession continues to push toward relatively low growth rates. Although the time horizons do not match exactly, the forecast comes in on the more pessimistic side of other predictions but like them, it does show moderate growth for the year.

The slope change had only a slight impact on the probability of a recession. Using the yield curve to predict whether or not the economy will be in recession in the future, we estimate that the expected chance of the economy being in a recession next October is 2.24 percent, up from last month’s 2.12 percent and just above August’s 2.23 percent. So although our approach is somewhat pessimistic with regard to the level of growth over the next year, it is quite optimistic about the recovery continuing.

The Yield Curve as a Predictor of Economic Growth

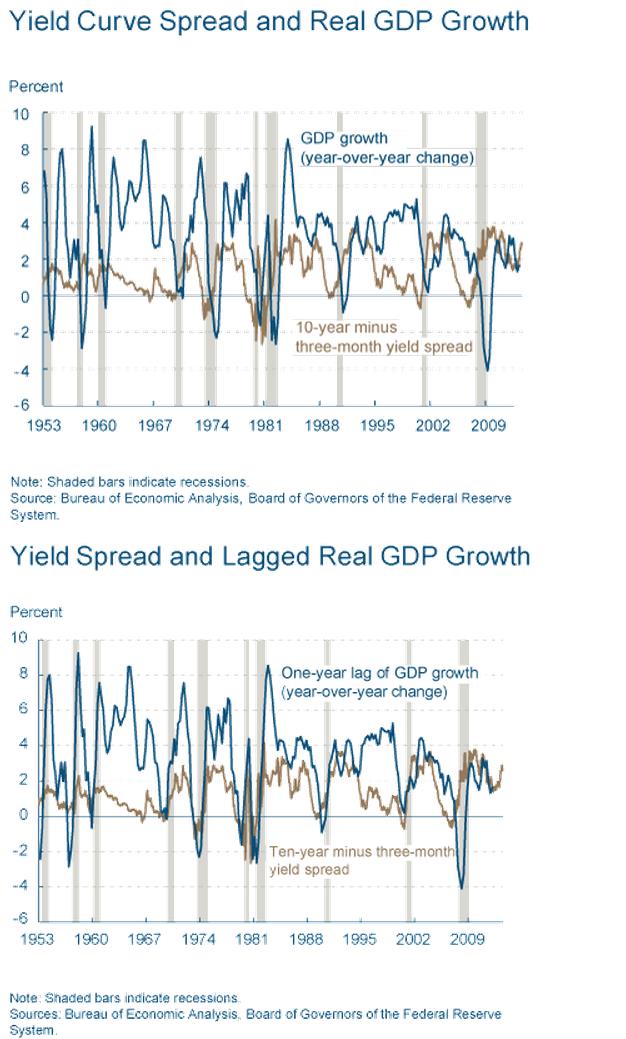

The slope of the yield curve—the difference between the yields on short- and long-term maturity bonds—has achieved some notoriety as a simple forecaster of economic growth. The rule of thumb is that an inverted yield curve (short rates above long rates) indicates a recession in about a year, and yield curve inversions have preceded each of the last seven recessions (as defined by the NBER). One of the recessions predicted by the yield curve was the most recent one. The yield curve inverted in August 2006, a bit more than a year before the current recession started in December 2007. There have been two notable false positives: an inversion in late 1966 and a very flat curve in late 1998.

More generally, a flat curve indicates weak growth, and conversely, a steep curve indicates strong growth. One measure of slope, the spread between ten-year Treasury bonds and three-month Treasury bills, bears out this relation, particularly when real GDP growth is lagged a year to line up growth with the spread that predicts it.

Predicting GDP Growth

We use past values of the yield spread and GDP growth to project what real GDP will be in the future. We typically calculate and post the prediction for real GDP growth one year forward.

Predicting the Probability of Recession

While we can use the yield curve to predict whether future GDP growth will be above or below average, it does not do so well in predicting an actual number, especially in the case of recessions. Alternatively, we can employ features of the yield curve to predict whether or not the economy will be in a recession at a given point in the future. Typically, we calculate and post the probability of recession one year forward.

Of course, it might not be advisable to take these numbers quite so literally, for two reasons. First, this probability is itself subject to error, as is the case with all statistical estimates. Second, other researchers have postulated that the underlying determinants of the yield spread today are materially different from the determinants that generated yield spreads during prior decades. Differences could arise from changes in international capital flows and inflation expectations, for example. The bottom line is that yield curves contain important information for business cycle analysis, but, like other indicators, should be interpreted with caution. For more detail on these and other issues related to using the yield curve to predict recessions, see the Commentary “Does the Yield Curve Signal Recession?” Our friends at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York also maintain a website with much useful information on the topic, including their own estimate of recession probabilities.